Communities must heal to move forward

Communities need to heal in order to move forward. That was the key message from a community dialogue held in Bonteheuwel on Saturday.

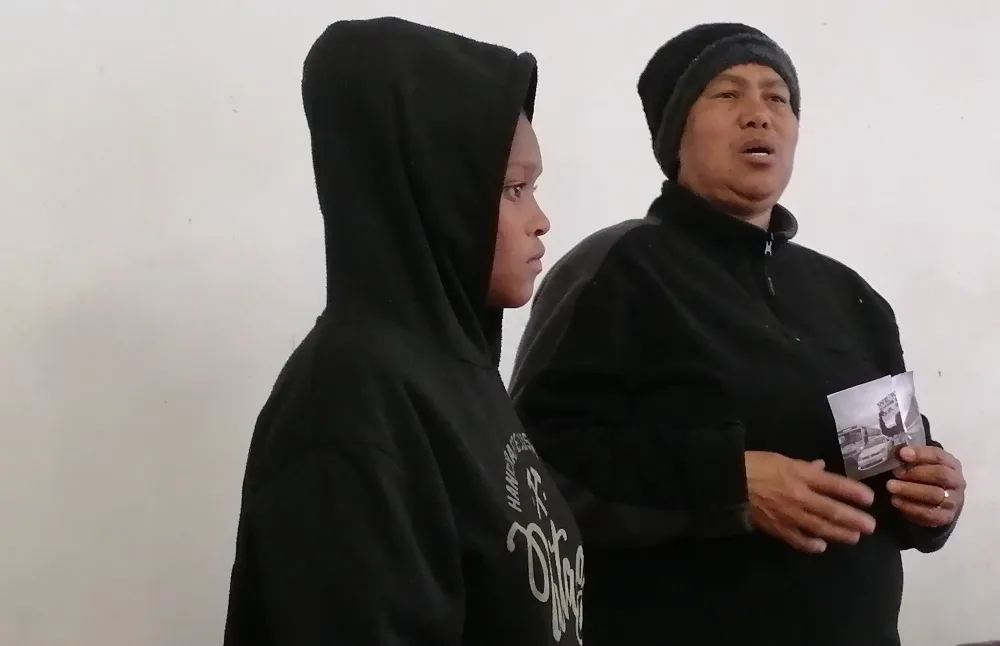

About 50 residents from Bonteheuwel and Kensington attended the dialogue, which was held at Boundary Primary School by the Women’s Assembly Movement (WAM), the Institute For Healing of Memories, the Bonteheuwel Development Forum, the Bonteheuwel Neighbourhood Watch, community health-care workers, and Boundary Primary’s governing body.

It was a chance for the residents to speak out about problems in their neighbourhoods, and drugs, crime, abuse, inequality, and a lack of resources were among the top issues they identified.

Cape Flats communities experienced a lot of trauma with death and violence never far away, said WAM chairperson Henrietta Abrahams.

“As communities, we have individual pain but also collective pain and trauma,” she said, adding that neighbourhood watch members were often directly affected by residents’ trauma as they were usually first on the scene.

Madoda Gcuadi, from the non-profit Institute For Healing of Memories, said there was intergenerational trauma in communities that still felt the impact of Apartheid.

“People are in pain. The impact of poverty has resulted in a lot of violence. If you are hungry, you will find ways to survive. When you have no economical means to live, you will find a way.”

Nazreen Steyn, of Bonteheuwel, said children sold drugs at school and had no respect for their teachers.

“Teachers are all leaving the country so what will happen? Parents are absent and grandparents have to look after the grandchildren,” she said.

John Lawrence, of Bonteheuwel, said: “The impact that the use of drugs has at school is so bad. Social grants are now being used to pay for drugs. When it’s pay day, you see the fathers of the kids or the children pushing their parents for their pension.”

He added: “Violence affects all of us, even if it doesn't happen to us. When you see something happening, we feel like we need to get involved because we have emotions. You can't just be a bystander because you feel guilt and shame. We end up being afraid and weak. We have no voice anymore because of crime. In many instances, we’ve changed our behaviour and go into cocoons when we see something happening because you think of your life and family.”

Mr Gcuadi said structural, cultural and direct violence made up a “triangle of violence”. While direct violence was felt from something like crime and cultural violence related to oppression people felt from belief systems, structural violence referred to abuses by those in power and it was visited on the Cape Flats by the lingering effects of Apartheid’s oppressive laws.

“Poverty and unequal education are still rife. Apartheid made sure that people were submissive to laws and policies. It is painful to understand that people still feel pain and are still separated. Everywhere people are shooting and killing one another now. Laws of separation are still there. Why are there townships and cities? That means we are not equal as South Africans.”